- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Digital work instructions change a shop’s culture

Immediate access to process information trains, empowers, and increases employee accountability

- By Sue Roberts

- March 21, 2018

- Article

- Management

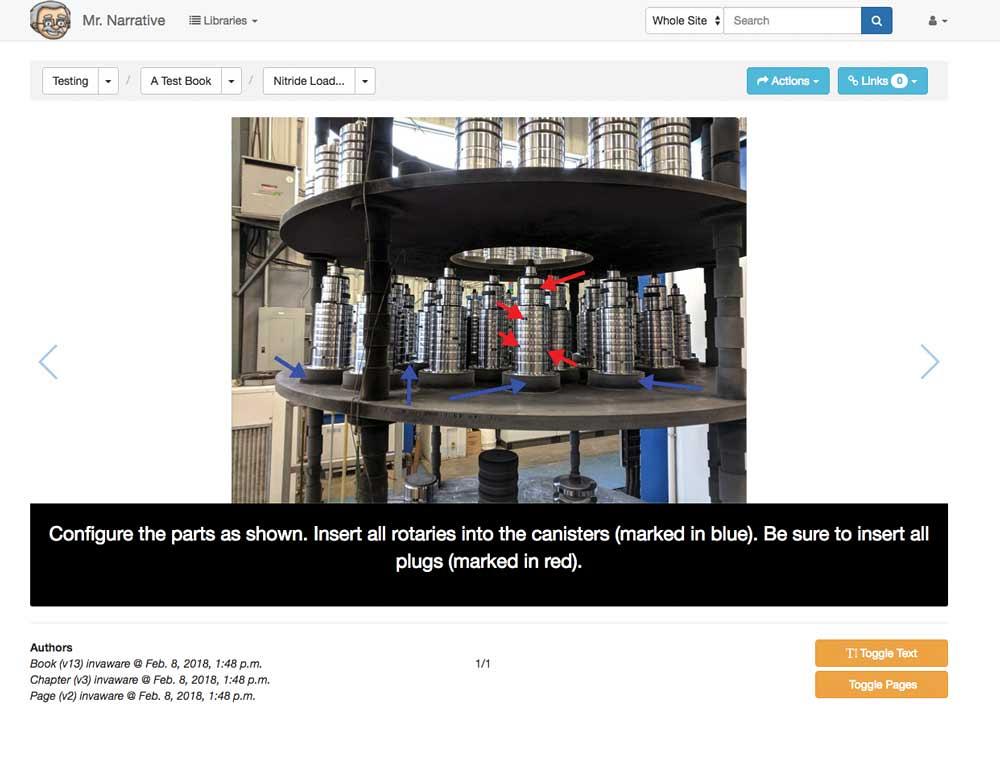

Step-by-step work instructions are developed by taking a photo and adding a line or two of directions.

Companies in the metalworking field continually strive to bolster the workforce. They work hard to educate the next generation to the realities of today’s manufacturing and the potential for meaningful, lucrative careers. As positions vacated by retiring industry members are filled with less experienced people, another challenge rears its head: How can the knowledge from the exiting, accomplished individuals be retained by the company and transferred in an efficient, effective manner?

Work instructions seem like the logical answer. In fact, any company that has gone down the documentation path of ISO certification has worked through the policies and procedures sections and spent time developing step-by-step actions, or standard operating procedures (SOPs), to capture this knowledge on each process.

Although this is a good step towards information maintenance and transfer, the initial recording of these steps and keeping them up-to-date can be cumbersome. And there are other problems.

One issue is that with today’s rapidly moving manufacturing environment, documents can become outdated at an alarming pace. Production specifications for a product don’t wait patiently for new information to be recorded and disseminated. Changes need to be made and pushed forward very quickly.

The age of the new members of the industry can be another issue. Younger folks grew up in a world of electronics and digital platforms that allow them to research and answer questions as they need the information. They learn in a different manner than those who started in industry 20 or 30 years ago.

Dan Savvidis, sales manager at Invaware Corp., an Ontario company specializing in software to help companies develop and manage electronic work instructions, said, “We find similar struggles regarding work instructions in shops from 10 people to 10,000 people. In many cases, SOPs sit in dusty binders on a shelf and typically do not have an electronic element. If there are electronic work instructions, they often reside in Excel or Word documents that’s aren’t easily accessible or searchable. And in either case, they aren’t kept up-to-date and aren’t often used.

“Work instructions are only good if they are used, and they are only as good as the information that they have recorded.”

Immediate Information Access

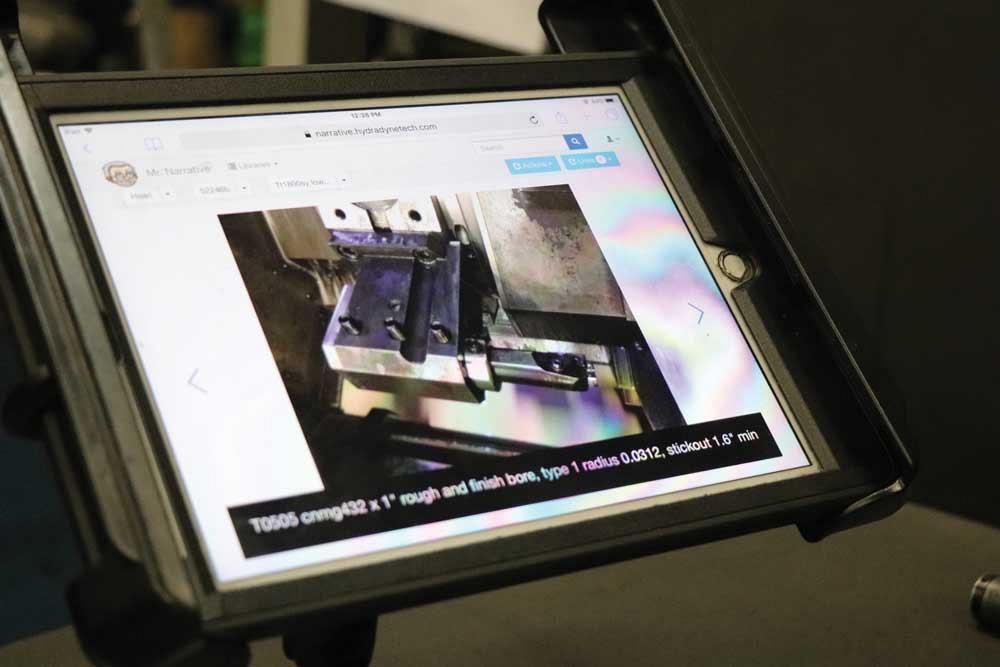

Digital work instructions such as the company’s Mr. Narrative™ are designed to capture step-by-step actions, make them readily available to everyone who may need them via tablets or other electronic devices, and eliminate the difficulty and time lag involved in keeping them up-to-date.

“One of the main things we focus on is getting a company to switch from an information retention mindset to a culture that offers information on demand,” said Mike Ulch, president and co-founder. “That kind of culture and information availability empower anybody to do any task at any time. It’s like giving them a company-specific Google™ to search for what they need.

“It creates a culture shift where employees go from saying, ‘That’s not my job’ to actively looking up directions and saying, ‘I didn’t know how to do that but I can get it done.’ It creates a sense of empowerment.”

To create these instructions, Savvidis said that they encourage bottom-up content creation that captures the expertise of experienced employees. “For example, when operators create the content, they really take ownership and pride in developing the work instructions. When someone accesses and uses the instructions on their own instead of having someone bark instructions that demand they do a job in a certain way, they take pride in their ability to produce, have ownership in their job, and retain more of the information.”

Build from the Floor Up

“An old method of developing work instructions might include taking pictures, writing down the instructions, and taking them to the office for formatting, printing, and inclusion in a binder. Electronic work instructions built from the shop floor up don’t go through layers of people who might not understand what they’re looking at. And instructions are created and available in real time for everyone to start using,” said Ulch.

To create the work instructions an operator can take a photo with an iPad®, tablet, or cellphone; add a line of instructions; and repeat for each step required. Annotations like arrows, circles, and colour-coding can be added to photos to highlight specific areas, help clarify a direction, or indicate a need for caution. All information such as correct tools and specifications required to do the job should be part of the document. Changes to existing work instructions can be made in the same way when updating is needed.

Every entry and change is recorded as a version of the work instruction. This task complies with ISO requirements, maintains a complete history, and makes it easy to identify when and who was involved. The documentation process can be set up so a moderator reviews each entry before it is pushed live.

Entries become part of a database. A library scenario is used to describe the different levels of information in this software. Each photo and description is referred to as a page, the pages are collected in a chapter. The chapters can be collected in a book that includes the work instructions for a specific type of job or department, and the book is located on a shelf with similar books. For example, the books of work instructions for milling projects can be on one shelf and those for accounting can be on another.

Content is searchable within predetermined parameters. Appropriate permissions can be built into the system to keep individuals from accessing unauthorized data.

Focus on Digital Only

The company encourages using only the electronic work instructions to train both new or temporary employees and current employees moving from one machine or process to another. It saves pulling an experienced person off the job to train, and digital training has a much better chance of engaging workers accustomed to using personal electronics.

Ulch said, “The trainee only uses this application to find and absorb needed directions and data. If there are questions, he or she goes to the supervisor who shows them where to find the information in the database. If the information is missing, it can be added. If it isn’t clear enough, it can be changed to make it usable on its own.

“We’ve noticed that when using digital work instructions, employees, especially the younger generation, will actively look for more information. When they have a few minutes of downtime, they start looking up the next part and reading about the steps they need to take.”

Beyond virtually eliminating training time, electronic work instructions can help fine-tune overall accuracy. Ulch said that one company reported that specific, accessible work instructions helped them reduce non-compliant parts from a daily average of eight down to one. Empowering the employees to seek answers to any question and move forward on their own increased accountability and attention to detail.

Savvidis said, “A byproduct of an audit trail that is built into digital work instructions is that any company performing some type of scientific research or developing experimental items or prototypes can use it for documentation. It can make the claims process easier if you are working with a government program. It is easy to go back into the software and present each step of the process.”

Use Good Existing SOPs

Moving from paper to digital work instructions can require a coup. Someone needs to dictate that work instructions will no longer be kept in any other form and champion the project.

If a company has undergone regular ISO audits, incorporating existing work instructions can be a good place to start. The information can be digitized and provide the base of the digital system. If existing work instructions aren’t up-to-date, they still can be digitized but kept in the background for reference as needed.

“You want to update all your processes when you make this kind of change. There is no point in entering inaccurate data into the system,” said Savvidis. “We can import data that isn’t necessarily current, but we recommend importing it into a hidden library that keeps track of what has and hasn’t been done when redoing instructions.”

Putting the digital instruction to use is easy with the younger generation. Acceptance by the more mature employees may take a little longer, but once the system is implemented, the immediate availability of information and the control it provides typically turn it into a well-used and welcome tool.

Savvidis said, “A lot of people aren’t technically inclined, and it takes a little longer for them to adopt these types of changes. But they are happening all around them whether or not they like it. We’ve seen that after a few months, you’d have to pry the tablet out of the hands of the most seasoned employee.

“Once companies start the process, they ramp up quickly. One 100-employee company had nearly 78,000 pages after one year. You can imagine putting that in a binder somewhere and making it searchable. As of now, pages of their work instructions are loaded 100 times a day per employee.

“Digital work instructions really do change a company’s culture and protect its information. They empower the employees to share information and take more ownership of their actions and secure the knowledge that contributes to a company’s success. I don’t think people realize how much information their employees retain until they see it in an electronic format.”

How Digital Work Instructions Change a Company

A switch to digital work instructions changes more than a company’s culture. Here are some statistics from companies that implemented them:

- Scrap was reduced from 1.6 to 0.9 percent of revenue.

- Training time was cut by more than 50 per cent plus. Plus, the amount of information each employee has to retain was reduced.

- Overall plant efficiency increased 5 per cent.

- Employee retention increased by 10 per cent due to fewer frustrations and improved engagement.

- The amount of time to file claims for the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) government program was reduced by 20 per cent

- The claim amount from SR&ED increased by 25 per cent.

Invaware Corp., www.invaware.com

About the Author

Sue Roberts

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-227-8241

Sue Roberts, associate editor, contributes to both Canadian Metalworking and Canadian Fabricating & Welding. A metalworking industry veteran, she has contributed to marketing communications efforts and written B2B articles for the metal forming and fabricating, agriculture, food, financial, and regional tourism industries.

Roberts is a Northern Illinois University journalism graduate.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

Automating additive manufacturing

Sustainability Analyzer Tool helps users measure and reduce carbon footprint

CTMA launches another round of Career-Ready program

Sandvik Coromant hosts workforce development event empowering young women in manufacturing

GF Machining Solutions names managing director and head of market region North and Central Americas

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI