Associate Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

5 myths of sawing soft materials

Cutting soft materials can be just as challenging as hard materials

- By Lindsay Luminoso

- March 6, 2024

- Article

- Fabricating

While true for all materials, failing to run the proper feeds and speeds when sawing soft materials can cause problems. Cosen Saws

Fab shops often work with many different types of materials, from the softest aluminums to the hardest INCONELs and everything in between. For fabricators with lots of experience sawing soft materials, it can be a smooth process that yields successful results. However, not all operators have the skill or knowledge base to effectively cut these types of materials on a standard industrial band saw. The following are five common myths that sawing industry experts hope to dispel.

Myth No. 1: Soft Materials Are Easy to Cut

It’s no secret that cutting hard materials like titanium, stainless steel, or even INCONELs is difficult. By comparison, many people believe that soft materials are easier to cut. This is not necessarily the case.

“Everybody feels that with soft materials, they should be easy to cut,” said Russell Chibe, territory manager, Midwest, at Cosen Saws, Charlotte, N.C. “Manufacturers go into it with the idea that they can just turn the saw on, the head drops out, and it starts to make the cuts. While it is true for all materials, if you don't run it at the proper feeds and speeds, you're going to get yourself in trouble. This is especially important for soft materials.”

Just because it’s soft, it doesn’t mean it is easy to cut. For example, many operators underestimate softer materials and end up stripping the teeth off the blade. This is true for aluminum, but it also can occur with brass and copper.

“These materials are gummy,” said Chibe. “That gumminess means that the material can load up into the gullet, which can create problems. If you fill up that gullet before it is out of the cut, this can lead to tooth strippage.”

Soft materials have unique characteristics that make sawing a challenge. It’s important to adjust cutting parameters to match the material being cut.

“If you don’t use the correct parameters, you are going to have as many problems cutting something like aluminum as you will with something such as a high-alloy material,” said Jay Gordon, North American sales manager, saws and hand tools at The L.S. Starrett Co., Athol, Mass.

Myth No. 2: It’s OK to Use the Same Blade and Parameters for Many Different Materials

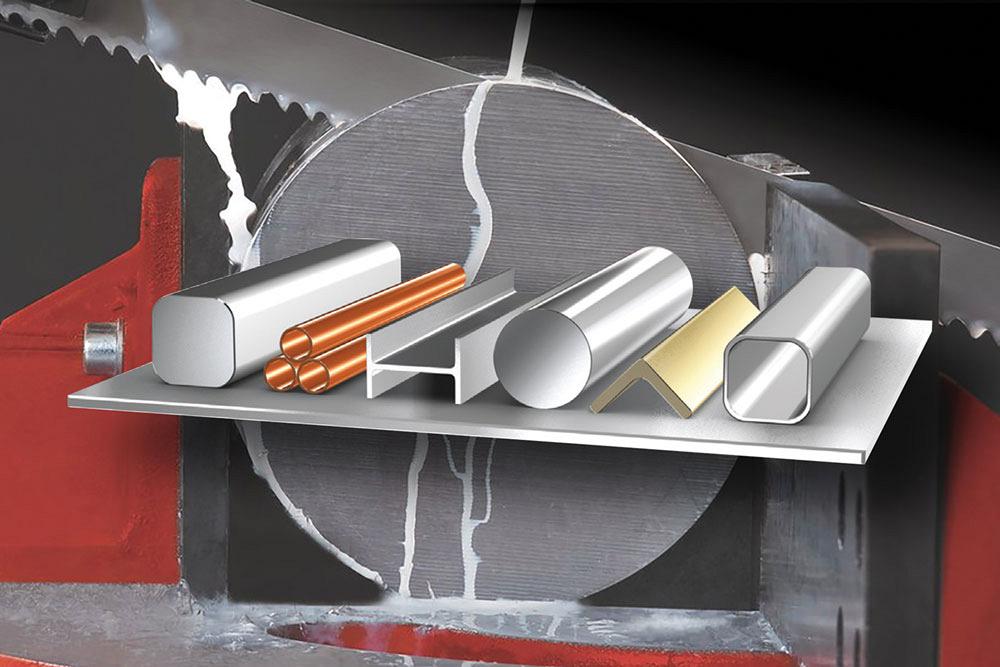

A soft material is a soft material no matter who cuts it. Fabricators, especially job shops, often cut a bit of everything, whether it’s tubing, angle, channel, or plate, in a range of materials.

“It can be very tempting to use one blade for everything,” said Gordon. “However, without the proper tooth pitch, that can be a problem. It’s a wide swing, and everything is contingent on the type of material being cut. Even within the softer materials, aluminum is going to cut different than copper, brass, and other non-ferrous softer-type materials. It’s a matter of matching up the blade speed, feed pressure, feed rate, and choice of blade with the type of material.”

Check out our guide to tooth pitch

The experts cited instances where fabricators cutting a piece of steel will switch over to aluminum, and rather than adjusting the sawing parameters for the softer material, they just throw it on the machine and start cutting. Doing this will compound any problems. Why? The pressure needed to force teeth into a piece of aluminum is significantly less than that of stainless steel and other harder materials. Without adjustment, fabricators cannot expect a successful cut.

Aluminum will cut differently than copper, brass, and other soft non-ferrous materials. It’s a matter of matching up the blade speed, feed pressure, feed rate, and choice of blade with the type of material. Starrett

“Some saw operators are not aware of the correct parameters,” said Jens Thieme, chief technology officer, WIKUS Canada Ltd., Mississauga, Ont. “The saw blade and tooth pitch are specific to the material being cut. [When] coupled with the wrong speeds and feeds for the application, [cutting] can be very challenging.”

The experts agree that working with a knowledgeable saw blade or machine manufacturer can be a great starting point to ensure that all parameters fit the application. Getting technical help or personalized training sessions also can help ensure a successful cut.

Myth No. 3: A Carbide-Tipped Blade Is Always the Best Option

There is a lot of hype around carbide-tipped saw blades, and for good reason. But does that mean they are the best option for soft materials? Not so fast.

“There is really only one reason to go with carbide, which is more expensive than bimetal, and that’s if you are trying to extend blade life, and even then, it might not be the best choice,” said Chibe. “However, if you are cutting something abrasive, like an aluminum casting, carbide is a good option because it can withstand the abrasiveness a lot better than bimetal.”

For the most part, carbide-tipped blades hold up better than bimetal blades, but again, they are often much more costly, and the cost isn’t necessarily justified.

“Carbide-tipped makes sense for solids but not something like aluminum tubing. For that, you would typically want a bimetal blade,” said Gordon. “In theory, you can technically even use a carbon blade, but practically speaking, bimetal is the way to go.”

Myth No. 4: Chips Are the Only Indicator of a Problem During the Cut

Chips are an excellent indicator of a problem during the process. A few specific visual characteristics can help fabricators diagnose the issue.

“If you are getting orange or purple chips, they are coming out smoking or glowing, you are overfeeding and running the blade too fast,” said Chibe. “If you get more of a dust-like chip or something very small and thin, that’s a sign you aren’t feeding enough, or you might be running the blade too fast. You want a silver, curly chip.”

When cutting aluminum, low-carbon steel, bronze, copper, brass, or anything soft, the chip should be of decent size in the shape of the numbers six or nine.

Chips, however, aren’t the only way to detect trouble. The material’s surface finish also can indicate a problem.

With smaller materials, you generally want more teeth per inch, and larger materials, less teeth per inch. If you are working with structural steel, H-beam, round tubing, square tubing, angle iron, there are some options available that offer a different tooth shape that will create different rake angles. Wikus Canada

“If the cut is rough, crooked, bowed, or looks like a dish cut, these are all indications the blade is loaded up, feeds and speeds are incorrect, or the blade has the wrong tooth pitch,” said Gordon. “This is a quick giveaway.”

If it’s a matter of gullets filling up and not clearing out, coolant is a great way to limit this problem. A good coolant mixture and flow will help control heat and limit gumminess.

Thieme added that a staggered cut or wash boarding can alert fabricators to an issue. He also noted that it’s important to follow how the chips are being evacuated—if they are coming out of the cutting channel or if longer chips are getting stuck.

“Another indicator is sound,” said Thieme. “You can hear if there is an issue with the performance of the saw. It’s not harmonized.”

Myth No. 5: Always Slow Down When a Problem Arises

Fabricators that slow down when something goes wrong while cutting soft materials on the band saw could be doing more harm than good.

“A lot of operators, when they tend to get nervous, their first inclination is to slow it down,” said Chibe. “This can be disastrous for soft materials. Soft materials should usually run at 250 to 300 FPM. So when you slow it down, this will only create more problems.”When cutting soft materials, a general rule of thumb is to cut them faster than the harder materials. And when it comes to cutting aluminum, fabricators should go as fast as the band saw will allow.

“If you run too slow, the blade might just stop in the middle of the cut because you don't have enough torque to push the blade through the material,” said Thieme.

Associate Editor Lindsay Luminoso can be reached at lluminoso@fmamfg.org.

Cosen Saws, www.cosensaws.com

The L. S. Starrett Co., www.starrett.com

WIKUS Canada Ltd., www.wikus-canada.ca

About the Author

Lindsay Luminoso

1154 Warden Avenue

Toronto, M1R 0A1 Canada

Lindsay Luminoso, associate editor, contributes to both Canadian Metalworking and Canadian Fabricating & Welding. She worked as an associate editor/web editor, at Canadian Metalworking from 2014-2016 and was most recently an associate editor at Design Engineering.

Luminoso has a bachelor of arts from Carleton University, a bachelor of education from Ottawa University, and a graduate certificate in book, magazine, and digital publishing from Centennial College.

subscribe now

Keep up to date with the latest news, events, and technology for all things metal from our pair of monthly magazines written specifically for Canadian manufacturers!

Start Your Free Subscription- Trending Articles

Aluminum MIG welding wire upgraded with a proprietary and patented surface treatment technology

CWB Group launches full-cycle assessment and training program

Achieving success with mechanized plasma cutting

Hypertherm Associates partners with Rapyuta Robotics

Brushless copper tubing cutter adjusts to ODs up to 2-1/8 in.

- Industry Events

MME Winnipeg

- April 30, 2024

- Winnipeg, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Windsor Seminar

- April 30, 2024

- Windsor, ON Canada

CTMA Economic Uncertainty: Helping You Navigate Kitchener Seminar

- May 2, 2024

- Kitchener, ON Canada

Automate 2024

- May 6 - 9, 2024

- Chicago, IL

ANCA Open House

- May 7 - 8, 2024

- Wixom, MI